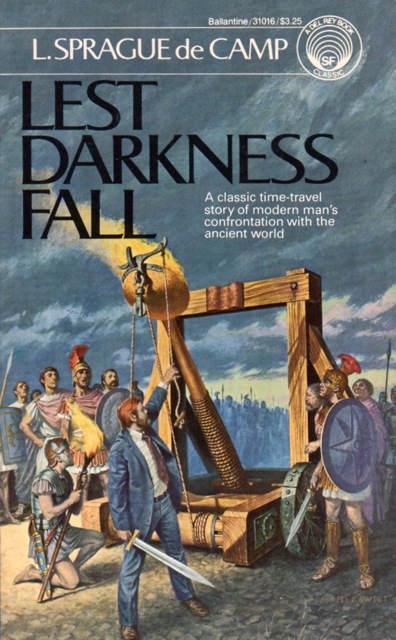

Now that I have remembered this blog, I have another review to post. I recently finished Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp (1907 – 2000). I read the Ballantine/ Del Rey 1983 edition with cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. I think the story was first published in periodical format in 1939, but the final novel format was released in 1941. I think it is an essential read for vintage science fiction readers. Generally, it is a story of time-travel and alternative history.

Now that I have remembered this blog, I have another review to post. I recently finished Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp (1907 – 2000). I read the Ballantine/ Del Rey 1983 edition with cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. I think the story was first published in periodical format in 1939, but the final novel format was released in 1941. I think it is an essential read for vintage science fiction readers. Generally, it is a story of time-travel and alternative history.

This is only a 208 page book, but it reads like there are many more pages. There is a lot of Roman/Gothic history involved in this novel and any familiarization with any of the locations or major players of the time is helpful. Any knowledge of languages and/or politics of that time just enhances this read quite a bit. As it is, most contemporary readers are really not all that familiar with the details of the year 535 and therefore, there may be some difficulty accessing the setting. That being said, I suspect one could muddle through with knowing just the main drift of history of this 6th Century.

Martin Padway is the main character. He is an American archeologist visiting Rome in 1938. Events transpire to send him back in time to Rome 535. Honestly, de Camp grants way too much skill and knowledge to Martin. This is my main criticism of the book, in one sense. Padway is an archeologist so it stands to reason that he has a solid knowledge base in a number of historical spheres. Yet, the things Padway is able to accomplish seems to extend even beyond what a good archeologist would have knowledge about. Indeed, it would be better to say Padway is a very intelligent polymath who specializes in archeology and clearly his pastimes are all of similar scholarly research. This includes a hefty base of political theory, languages, military tactics, and engineering. Now, the only sense in which this is a useful criticism, though, is the one wherein we are considering how realistic this story and character might be. But I did say that he is zapped back in time to 6th Century Rome, so I am quite sure discussions on “realism” may need to be adjusted.

Readers, then, can comfortably approach the novel knowing the most advanced technology that Padway accesses is that of the 1930s and that he is an adept, brilliant archeologist. What can he do in Rome? Well, he keeps his head remarkably well for someone experiencing sudden time-displacement. He takes stock of his situation and realizes he needs to work to maintain basic survival items. By applying modern understanding and historical knowledge, Padway carves his own survival out by being an inventor. This is pretty fun, because most time travel novels are all caught up in the “what-if” scenario of “changing the timeline.” Well, Padway’s goal becomes one of changing the timeline. He realizes he is in/on the cusp of the Dark Ages (hence the title) and he is attempting to stave off and avoid the collapse of civilization.

Some things to admit: yes, historians have been arguing SINCE the “dark ages” about when they were, why they were, and if they were. So, if you are an historian with a particularly emotional bent on one of these positions, try not to let it get in the way of your reading enjoyment. Further, I know this story could spark discussions of plausibility about one man’s efforts, the so-called Butterfly Effect, the amount of luck and timing involved, etc. In other words: who can really set aside enough disbelief that they can follow one guy’s actions to stop the fall of civilization? How could anyone even think one chap could do enough to alter the timeline so drastically?

That is why this novel is essential reading – because it asks so much of the character! I love the lofty goal that de Camp throws at Padway and I like that de Camp feels he is writer enough to deal with the problematic and make it interesting! It is not always about the feasibility of a storyline that makes it a good read, but sometimes it is the daring in tackling a huge scenario that makes a novel worthwhile.

Now, we know Padway is thinking first about himself and his survival. He concludes, not unreasonably, that his personal success rate is tied to society’s survivability. The one thing that all schoolkids even know about the “dark ages” is that it was a loss of science and art and progress. Therefore, still very reasonably, Padway realizes he needs to become an “inventor” and at one heckuva pace! Now, certainly, he is and is not the true “inventor” of things – but that’s picayune. A large portion of the novel is then tied up with Padway’s efforts to get his inventions off the ground in 6th Century Rome.

Interestingly, the first inventions of Padway’s are a type of brandy and a newspaper. So, naturally, Padway has to have come back in time with a workable knowledge of ink, metallurgy, rudimentary chemistry, and paper-making. It is not easy for Padway, but if the reader is honest, the whole situation would be much more difficult. Again, how are we talking about “realism” here, anyway? These are the inventions, Padway manages it, we move onward. Along with these two “physical” inventions, accounting and mathematics are also some of the very first influential “breakthroughs” Padway introduces to the society.

Frequently, throughout the novel Padway is accused of being a future-seer – a concept that has varying degrees of concern according to the perspective (heathen, Christian, etc.) of those who meet him. This knowledge of history comes in very useful as Padway is able to have foresight in order to be in the right place and the right time or to convince people of his ideas based on the fact that he does, actually, know certain outcomes.

Padway sighed. “You’re as bad as Belisarius. The few trustworthy and able men in the world won’t work with me because of previous obligations. So I have to struggle along with crooks and dimwits.”

Darkness seemed to want to fall by mere inertia— – pg. 140, chapter XI

Somewhere past halfway, the novel changes from focusing on Padway’s personal survival and his efforts to keep himself safe and sound, into a focus on his efforts to save civilization. The shift to the broader scope is not ridiculous, but as I reader, I was somewhat saddened to lose the individual struggle plotline. Suddenly, Padway is on horseback and leading armies and debating military tactics and rubbing elbows with princesses, kings, generals, and so forth. The last quarter of the novel is really a military tactics study in brief – the use of pikes, lances, the strategic retreat, flanking procedures, etc. Though I enjoy these subjects, it felt a little bit strained from the origin of the novel, and so I was a little less engaged with my reading. If there is a point where my disbelief finally got foothold, it was here: an American archeologist is just not going to be this excellent at off-the-cuff strategy and tactics as a field marshal.

Anyway, in 208 pages a lot gets invented. Its fun to watch Padway extricate himself from all the situations he finds himself in. Maybe de Camp makes the natives of the time a little more “unintelligent and forgiving” than they really were. And yes, Padway is definitely too smart. Overall, though, this is a strong novel and one I think I can recommend to most readers.

4 stars

Caviar by Theodore Sturgeon (1918 – 1985) was first published in 1955. Once again, I completed a 1950s book. This is a collection of 8 stories ranging from 1941 – 1955. The cover art for the copy that I read (1977 Ballantine) is by Darrell Sweet. Though Sturgeon did publish several novels, it is my understanding that he is famous for his short fiction.

Caviar by Theodore Sturgeon (1918 – 1985) was first published in 1955. Once again, I completed a 1950s book. This is a collection of 8 stories ranging from 1941 – 1955. The cover art for the copy that I read (1977 Ballantine) is by Darrell Sweet. Though Sturgeon did publish several novels, it is my understanding that he is famous for his short fiction. The Lure of the Basilisk by Lawrence Watt-Evans is the first book in The Lords of Dûs series. It was first published in 1980 – the copy I read is the 1987 edition. The cover art was done by Darrell K. Sweet.

The Lure of the Basilisk by Lawrence Watt-Evans is the first book in The Lords of Dûs series. It was first published in 1980 – the copy I read is the 1987 edition. The cover art was done by Darrell K. Sweet.