The Dreaming Earth by John Brunner was first published (as novel form) in 1963. I read the Pyramid Books first printing from February 1963 with cover art by John Schoenherr. It is a relatively short novel, 159 pages, but I feel like I did not get through the novel very quickly. The main character is Nicholas Greville, a UN officer in the Narcotics Department. The novel takes place in the U.S.A. presumably sometime in the not-too-far future. The situation that humanity faces is a severely dwindling supply of resources. There are too many people and not enough to go around. There has not, yet, been a catastrophic event, but humanity teeters on the brink of absolute horror (utter devastation, war, etc.) because the overpopulated planet (I think Brunner says just over 8 billion) is strained to the maximum. Apartments are stuffed, travel is very restricted, leisure is reduced to nothing. There are efforts to develop artificially-enhanced biotechnologies for growing food (projects for the sea, projects for the soil), but at the current rate, it is insufficient.

The Dreaming Earth by John Brunner was first published (as novel form) in 1963. I read the Pyramid Books first printing from February 1963 with cover art by John Schoenherr. It is a relatively short novel, 159 pages, but I feel like I did not get through the novel very quickly. The main character is Nicholas Greville, a UN officer in the Narcotics Department. The novel takes place in the U.S.A. presumably sometime in the not-too-far future. The situation that humanity faces is a severely dwindling supply of resources. There are too many people and not enough to go around. There has not, yet, been a catastrophic event, but humanity teeters on the brink of absolute horror (utter devastation, war, etc.) because the overpopulated planet (I think Brunner says just over 8 billion) is strained to the maximum. Apartments are stuffed, travel is very restricted, leisure is reduced to nothing. There are efforts to develop artificially-enhanced biotechnologies for growing food (projects for the sea, projects for the soil), but at the current rate, it is insufficient.

Brunner is an excellent author. He has a strong, academic and practical, understanding of how to build a novel. Reading a Brunner novel really ought to be required reading for all those college courses about “creative writing” and “novel writing” or whatever they are. Its all very well and good to take literature classes which dissect the novel and look at those annoying classics, but it is entirely different when its seen in practice in a 1960s science fiction novel. How is it different? It seems to me that when you take Nabokov’s literature class – he already has selected the measuring stick as the example. Its too tautologous – using the standards that create the novel characteristics as examples of novels that have those characteristics. Brunner’s novel is not one of “those” classics. It is a 1960s science fiction novel that is quite sincerely a product of its times – bursting with 1960s viewpoints. Further it has flaws – after all, I am only giving this book two stars. I suppose if you complain loudly enough, I might agree that it is a three star novel. The point is, it is not even close to a perfect novel. So, examining it ought to give potential writers clues on what succeeds and what fails and why this is all so.

Let me make a bit of a taxonomy for us:

- well-built structure with seamless movements

- diverse characters with complex issues: both novel-wide and individual

- red herrings and brick walls to confront characters and readers

- tightness of writing – the prose is clean, concise, and intelligent

One would look at this list and marvel that whatever novel I am describing is not five stars! Alternatively, what sort of beastly critic must I be if I am unsatisfied with these elements and still demand more from a work! Well, there are several reasons. The most major one being that Brunner is an Icarus-author here. He took on a problem (i.e. overpopulation/resources) and he took a contemporary situation (i.e. hallucinogenic drug-usage) and once airborne, he flew too close to that tempting, delicious, ever-drawing sun that is ontology. His ill-planned flight was not accidental, he knew precisely how high he was flying [pun intended] and in what direction.

He proves foreknowledge because in chapter fifteen, the main character meets with another character, Franz Wald, and they have a terse discussion on epistemological concerns. The one character says:

“Berkelianism is a completely hypothetical view which is inconsistent with human experience. I’m pragmatic when it comes to the question of reality or das Ding an sich or whatever you call it. Human experience indicates that there’s something external to our nervous systems which acts on our organs of perception, and whatever it may be in its own essence we have to accept that it’s there. But don’t let’s get sidetracked!” – pg. 97

Well, characters are not going to bring up Modern Philosophy unless their author knows where he is driving the plotline. Now, there are lots and lots of science fiction novels wherein the readers criticize the “science” of the novel. There are less overt opportunities to criticize a novel due to its metaphysics. Usually because authors do not so blatantly march toward it with such obvious intent of making a mess of it.

The novel itself begins with a quote from the Rig Veda:

The Heaven I have overpassed in greatness and this great Earth. Have I not drunk of the Soma?

Lo! I will put down this Earth here or yonder. Have I not drunk of the Soma?

Swiftly will I smite the Earth here or yonder. Have I not drunk of the Soma?

So the author (publisher?) wants the reader to know straight off that there is some sort of antagonism between the drug usage and the earth. And the main character is a UN official working in the Narcotics Department. Unfortunately, throughout the novel, we are not really given a clear idea of what lane Greville swims in. What is his role with the Narcotics Department? Basically, it seems rather self-assigned and vague. He just sort of spends his time thinking about the problem of “happy dreams” and complaining about it. “Happy dreams” are a powdered substance that is trafficked like a typical narcotic except for a few interesting features. The product seems to defy reasonable economics – since it has a set price, which is very low, and no one seems to know where it comes from – but there is always plenty to go around.

We meet Greville en route to a research facility wherein he has a case of the powered hallucinogenic chained to him. The facility is expecting his delivery because they are performing research/experiments on apes and such to discover whatever they can about the drug. Via the journey to the facility the reader gets hands-on knowledge of the scenery, that is, how the shortages are affecting things. This is a solid example of an author sneakily showing the reader things without lecturing them or bludgeoning them. An underlying tone throughout the novel occurs wherever Greville goes: every place he visits has a stressed, tired, or frustrated feeling about it. This is true at the facility where Greville delivers the “happy dreams.”

The director of the facility introduces Greville to another on-site researcher, Dr. Kathy Pascoe. Immediately, though Brunner stinks up the works by referring to this character as “the girl.” For convenience, the characters retire – after locking the facility down very well – to the Director Barriman’s living suite. There, conversations occur: Greville is given some insights into the “happy dreams” drug and some history of incidents at the research facility. This is somewhat how the storyline progresses for the rest of the novel. Greville goes to a location, conversations occur. The fact that he seems to have utter free roaming due to his Narcotics Department job moves the plot, but it also makes the character seem like he is chasing his tail at random.

This is one of the flaws of the novel, in my opinion. Events occur usually just adjacent to Greville. It always seems like he is in the thick of things, but simultaneously like he is late to the event or that the big item happened just off-stage. This just results in the reader following Greville around and having to listen to his very frequent frustrated ponderings. Greville talks a lot. Unfortunately, he does not say anything new and it all is very repetitive. Whenever Greville’s ponderings leave him stumped, he goes to another location and begins all over again.

A novel about conversations and thinking about the weird drug-use is not actually all that exciting to read. I just could not stand another time Greville feeling like “he needed to think.”

Nevertheless, throughout, Brunner has charming bits of wordworking. For example, I really liked the start of chapter fourteen:

When he awoke, streams of rain like straight steel legs were marching across the city to the rattle of a thunder like drums. – pg 86.

The climax of the novel comes when “the girl” Pascoe and Greville witness a “happy dreams” addict actually disappear. Then it just all becomes so undeniable and Pascoe and Greville validate what seems impossible and what Franz Wald might have been on the cusp of saying, if Brunner had a better grasp of metaphysics. The truth is, late in chapter twenty, Greville is struggling, once again, to formulate the situation to a group of listeners. Except that his explanation is awful to read-through. It shows Brunner was not ready for the metaphysics. Greville stumbles around and gropes for the explanation – presumably this is why Brunner has Greville do the talking – the scientists would, in theory, do it better. Since the characters cannot articulate more than their author can, Brunner has to have Greville explain matters.

The worst part is that the resolution is exactly what any decent reader suspected all along. This is okay in the sense that it is tidy and the structure of the novel suits. However, now it feels like the whole thing was a bit of a waste and maybe could have just been a short story. Maybe the short story could even be of a UN official just giving a press conference and shocking a few scientists. Anyway, the resolution confirms the utilitarianism that was suspected all along. It could be a tidy ending – except for the absolutely unworkable, illogical, bad-reasoning of the metaphysics of the novel. Brunner, I think, just wants to smush the concepts of subjective/objective reality together like Play-Doh and hope that in the smushing, the reader is not paying attention. In terms of author’s being ridiculous, this one is pretty dang unique of an example.

I like reading Brunner novels. I think he was a very good writer. This novel still has a lot of merit to it. However, its just such a fail in terms of reality, it almost feels like Brunner was hand-waving at things. Well, if you are only going to be dismissive of problems – do not attempt to tackle them and bring them in as the major elements of your story! I cannot understand what happened here, other than to give some credit to Brunner for the oddness of it all. Brunner fans only, OK?

2 stars

Murder in the Dark is the sixth novel in the Ishmael Jones series written by Simon R. Green. It was published in 2018 and I have read the previous installments of the series. Of note, the previous novel was exceptionally poor and I had not decided to continue with the series until much later when I realize I already owned this novel. Murder in the Dark is a step up from the previous novel (

Murder in the Dark is the sixth novel in the Ishmael Jones series written by Simon R. Green. It was published in 2018 and I have read the previous installments of the series. Of note, the previous novel was exceptionally poor and I had not decided to continue with the series until much later when I realize I already owned this novel. Murder in the Dark is a step up from the previous novel ( Amnesia Moon is Jonathan Lethem’s second novel. It was published in 1995. It is allegedly a novel that was worked together by the author from a variety of shorter, and somewhat similar, pieces he had already written. I think that is very apparent in this book, and for once, it is very unimportant because the finished product works with this sort of cobbling together. Some things right out of the gate: this is not a book for most readers. The readers who read novels that are the standard traditional linear form of the novel, orthodox in every way like a high school English class would learn, will not want to read this. I have seen this book referred to as psychedelic, as avant-, as post-, etc. Sometimes some readers definitely want to read this style of book. At other times, I can see this being the last thing a reader wants to look at. Either way, I would be very surprised if the traditional reader would be very pleased with this novel.

Amnesia Moon is Jonathan Lethem’s second novel. It was published in 1995. It is allegedly a novel that was worked together by the author from a variety of shorter, and somewhat similar, pieces he had already written. I think that is very apparent in this book, and for once, it is very unimportant because the finished product works with this sort of cobbling together. Some things right out of the gate: this is not a book for most readers. The readers who read novels that are the standard traditional linear form of the novel, orthodox in every way like a high school English class would learn, will not want to read this. I have seen this book referred to as psychedelic, as avant-, as post-, etc. Sometimes some readers definitely want to read this style of book. At other times, I can see this being the last thing a reader wants to look at. Either way, I would be very surprised if the traditional reader would be very pleased with this novel. Close Quarters is Michael Gilbert’s (1912 – 2006) first novel. It is also the first in his Inspector Hazlerigg series. I have never read anything by Gilbert before, but I do intend to read other novels by him. This novel was a strange thing. I felt like it was set-up to be a perfectly familiar “golden age” mystery placed in a typical English Cathedral setting. There is a campus, which is locked at night, a bunch of quirky intellectual canons and vergers, and associated gardeners. The dean of the whole place is fairly decent at being the dean, the reader supposes, but not too excellent at knowing how to deal with attempted murder and the like. The dean calls his nephew hoping for an unofficial, but still police-involved, assistance.

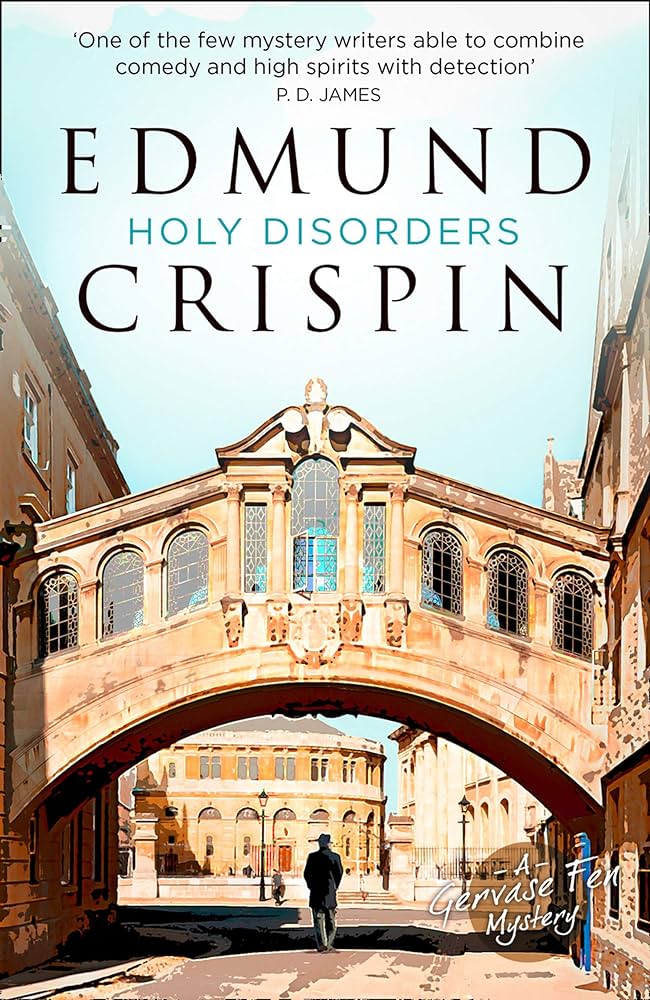

Close Quarters is Michael Gilbert’s (1912 – 2006) first novel. It is also the first in his Inspector Hazlerigg series. I have never read anything by Gilbert before, but I do intend to read other novels by him. This novel was a strange thing. I felt like it was set-up to be a perfectly familiar “golden age” mystery placed in a typical English Cathedral setting. There is a campus, which is locked at night, a bunch of quirky intellectual canons and vergers, and associated gardeners. The dean of the whole place is fairly decent at being the dean, the reader supposes, but not too excellent at knowing how to deal with attempted murder and the like. The dean calls his nephew hoping for an unofficial, but still police-involved, assistance. Holy Disorders by Edmund Crispin was first published in 1945. It is the second in his Gervase Fen murder mysteries. I read it a few days ago and I am giving it five stars. I really enjoyed this one, but I recognize that not every reader will tolerate it. Crispin (Robert Bruce Montgomery) was a heckuva writer. Allegedly he ran toward a rather bad end full of alcohol and ruined friendships. As an author, though, he produced at least two (I have read two so far!) excellent mysteries.

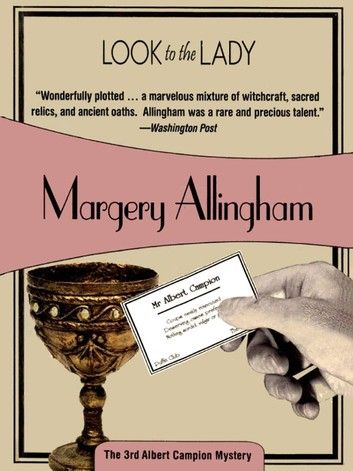

Holy Disorders by Edmund Crispin was first published in 1945. It is the second in his Gervase Fen murder mysteries. I read it a few days ago and I am giving it five stars. I really enjoyed this one, but I recognize that not every reader will tolerate it. Crispin (Robert Bruce Montgomery) was a heckuva writer. Allegedly he ran toward a rather bad end full of alcohol and ruined friendships. As an author, though, he produced at least two (I have read two so far!) excellent mysteries. The last quarter of this year has been very hectic and has involved a lot of travel. The travel has also had me in places lasting even two weeks at a time. Traveling ruins my concentration and focus for more scholarly activities. That also includes basic novel reading. There were a few minutes to spare very early in December and I was able to finish Margery Allingham’s Look to the Lady. This was first published in 1931 and is the third in the Albert Campion series. I read the Felony & Mayhem edition from 2006.

The last quarter of this year has been very hectic and has involved a lot of travel. The travel has also had me in places lasting even two weeks at a time. Traveling ruins my concentration and focus for more scholarly activities. That also includes basic novel reading. There were a few minutes to spare very early in December and I was able to finish Margery Allingham’s Look to the Lady. This was first published in 1931 and is the third in the Albert Campion series. I read the Felony & Mayhem edition from 2006.

It is difficult, I think, to write reviews of Agatha Christie novels. The most significant reason being that since they are so amazingly popular and well-known that there is not a whole lot left to “review” in 2023. Another reason is that much of these little novels is entwined in plot twists, red herrings, or key plot elements so that it could be easy to spoil the read for another reader. Beyond that, there are all the TV adaptations etc. that also color the contemporary reader’s image of Poirot and his author. It can be a bit sticky to try and separate some of these ideas out because they are just sort of homegrown things that do influence, rightly or wrongly, the actual reaction to the novel.

It is difficult, I think, to write reviews of Agatha Christie novels. The most significant reason being that since they are so amazingly popular and well-known that there is not a whole lot left to “review” in 2023. Another reason is that much of these little novels is entwined in plot twists, red herrings, or key plot elements so that it could be easy to spoil the read for another reader. Beyond that, there are all the TV adaptations etc. that also color the contemporary reader’s image of Poirot and his author. It can be a bit sticky to try and separate some of these ideas out because they are just sort of homegrown things that do influence, rightly or wrongly, the actual reaction to the novel. Back in October 2022, I started reading this Ray Bradbury collection. I thought it apropos for October-season. Well, I read the first three and half stories in the nineteen story collection and I put the book down for a year. I have tried to read Ray Bradbury several times in my life – the earliest in the early 1990s when I had Something Wicked This Way Comes and I could never bring myself to read very far in it. I eventually just got rid of that book in defeat. I do not dispute that Bradbury is an interesting author with skill. He is incredibly well-known and well-read and is usually considered among the greats of speculative fiction writers and American writers. So, here’s me with another unpopular opinion; I learned such things from Nabokov: Bradbury is not an author who’s writing works well for me.

Back in October 2022, I started reading this Ray Bradbury collection. I thought it apropos for October-season. Well, I read the first three and half stories in the nineteen story collection and I put the book down for a year. I have tried to read Ray Bradbury several times in my life – the earliest in the early 1990s when I had Something Wicked This Way Comes and I could never bring myself to read very far in it. I eventually just got rid of that book in defeat. I do not dispute that Bradbury is an interesting author with skill. He is incredibly well-known and well-read and is usually considered among the greats of speculative fiction writers and American writers. So, here’s me with another unpopular opinion; I learned such things from Nabokov: Bradbury is not an author who’s writing works well for me. I am in the middle of too many books. There are so many that I am reading for my profession, but then there are so many that I am reading for entertainment. And soon it will be October and I rather enjoyed the past years wherein I would read a few horror-genre items. So, of course, at the library last week I saw they had a copy of Deserter by Junji Ito and borrowed it. The obvious thing to do when the book stacks are avalanching – very much like a horror scene.

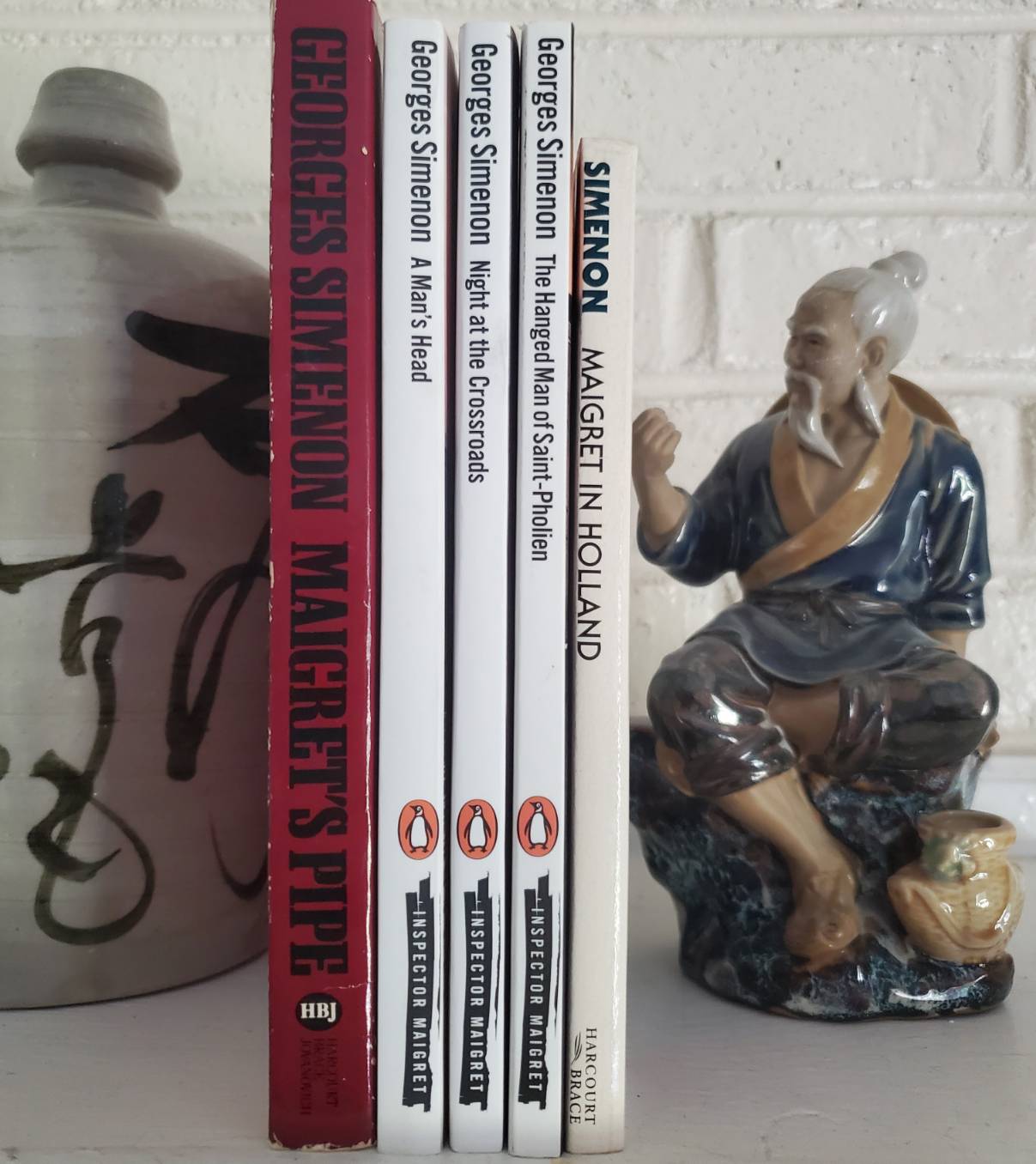

I am in the middle of too many books. There are so many that I am reading for my profession, but then there are so many that I am reading for entertainment. And soon it will be October and I rather enjoyed the past years wherein I would read a few horror-genre items. So, of course, at the library last week I saw they had a copy of Deserter by Junji Ito and borrowed it. The obvious thing to do when the book stacks are avalanching – very much like a horror scene. In contradiction to all of my complaints about crime and evil in my previous review, I snapped up an Inspector Maigret novel and jumped right back into the dark-side of humanity. I think reading a Maigret novel was a good poultice for me after all the emotional upheaval and drama of my previous read. Maigret’s endless solidity, internalizing, and lumbering around make any crime into a noir-esque style story. Yes, noir, because this one includes a girl, a sailor, cocaine, and a dog.

In contradiction to all of my complaints about crime and evil in my previous review, I snapped up an Inspector Maigret novel and jumped right back into the dark-side of humanity. I think reading a Maigret novel was a good poultice for me after all the emotional upheaval and drama of my previous read. Maigret’s endless solidity, internalizing, and lumbering around make any crime into a noir-esque style story. Yes, noir, because this one includes a girl, a sailor, cocaine, and a dog. One of the things that was challenging for me was keeping the characters and their names straight. Man, this is such a frequent problem for me. I so many times cannot keep track of characters and their names. Its always been a flaw in my reading. In this novel there are about five key characters. My main frustration with the novel was with constantly having to re-think who is who.

One of the things that was challenging for me was keeping the characters and their names straight. Man, this is such a frequent problem for me. I so many times cannot keep track of characters and their names. Its always been a flaw in my reading. In this novel there are about five key characters. My main frustration with the novel was with constantly having to re-think who is who.